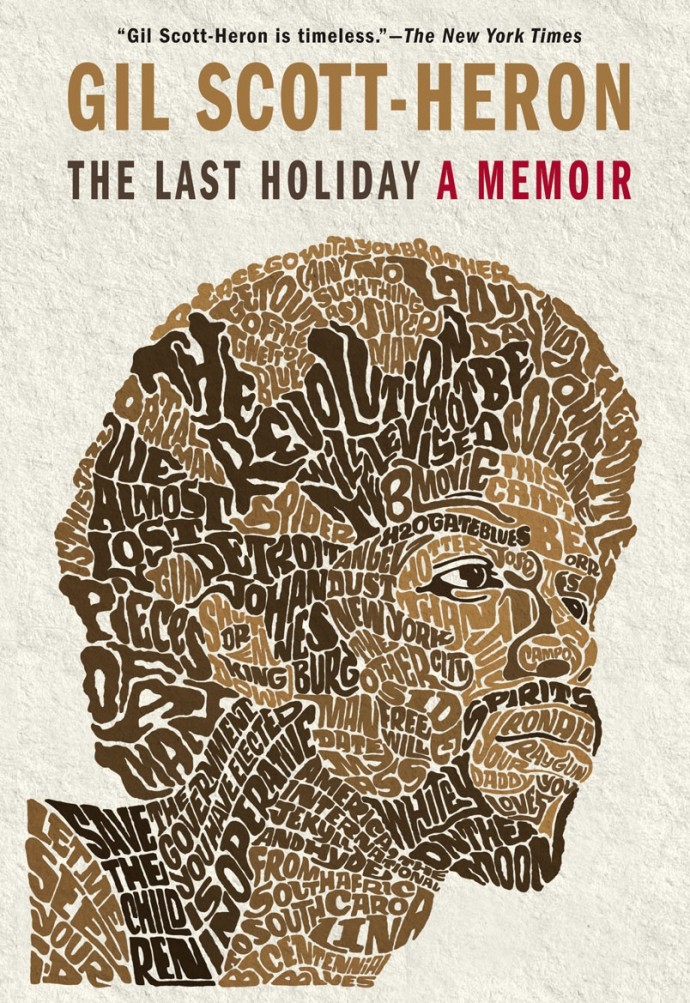

Every word was savoured. I started the book, read the first hundred pages, and had to start again – just so that I could drink in the words again. In my mind, The Narrator’s distinctive growl enunciated each word with absolute clarity and authority. I’ve taken months to complete the book, despite it being barely a shade over 300 pages from start to finish. The subject matter was just too important to me to rush, or to skip over any tiny detail. And, more poignantly, as I read the final words of the final chapter – as The Narrator bares his soul and makes a stark admission of his basic flaws as a human being – I realized that this was the last ‘new’ material I’d be consuming from Gil Scott-Heron.

From the painfully honest description of his upbringing, taking in the death of his beloved grand mother; through his checkered days in education, including his bucking the system and securing his first publishing deal while he should have been studying; to his ultimate realization that he has – as a father and a family man – failed to show the love that other people deserved from him… Gil Scott-Heron’s story is that of a single-minded rejection of ‘the stable path’.

But, while ‘The Last Holiday’ is on the surface a memoir detailing this life – the title belies one crucial difference. This is Gil Scott-Heron we’re talking about. It was never going to be a simple story.

Anchored in the middle of the book – and essentially providing the central thrust as to why Gil Scott-Heron put pen to paper – is the story of how Stevie Wonder helped to institute a national holiday in remembrance of Martin Luther King Jr, and our Narrator’s role in the events.

Any reader of this site will be well versed in the admiration I have for both Gil Scott-Heron and Stevie Wonder. They have each made their own unique and indelible mark on our musical landscape. Gil Scott-Heron – for some the Godfather of Rap, but to me always the Minister of Information – brought a political and social awareness to jazz, funk and soul that still resonates. Fine – he may not have been the only person to do this – but with tunes such as ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’ and ‘The Bottle’ he made a point, made it stick, and made it with a damn fine groove. As for Stevie Wonder – I simply can’t say enough about his ability to weave a sonic patchwork into something that is at once a slice of pop music, and at the same time being as emotionally naked as imaginable. I defy anyone to not be moved by the sound of a newborn Aisha on ‘Isn’t She Lovely’. I’m welling up just typing the words.

In this context, reading the description of admiration in its purest form which Gil Scott-Heron held for Stevie Wonder was like a basic affirmation of talent. It’s almost as though, through his words, Gil Scott-Heron managed to make the sum of their talents greater than the parts. Such sweeping praise for Stevie Wonder, be it in terms of his musical abilities, or his alchemistic ease with an audience, or his underlying humour just sticks when the praise is being heaped by someone with the innate ability to articulate his thoughts as Gil Scott-Heron.

I write this post on the eve of the 40th anniversary of the release of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Innervisions’. Tonight, during my evening commute, I selected the album on my iPod, cranked the volume up, and bathed in the sounds as my car crawled from New Jersey through Lower Manhattan. From the opening bars of ‘Too High’, the album makes a statement as being something truly special. This was Stevie Wonder – already master of the art of pop – finding something far richer to share. ‘Visions’, I maintain, is one of the most powerfully descriptive songs of the beauty of the visual side of everyday life – made all the more staggering by the fact that it was written by somebody who does not get to enjoy what he’s describing. As I entered the Holland Tunnel, taking me from New Jersey into New York City, I was fortuitously served up ‘Living For the City’ – a stark dissection of the perils of life in the urban metropolis.

‘New York, just like I pictured it… skyscrapers and everything’.

In ‘Higher Ground’, Stevie Wonder brings the funk, but brings it with a message of hope and redemption. In ‘He’s Misstra Know It All’ Stevie never ceases to make a point – essentially sticking it to the loud mouths of the world, and doing it with style and wit. Honestly – I don’t think there’s a spare note on the entire album. It’s simply perfect.

When Gil Scott-Heron heaps praise on someone, it’s because the praise is deserved. For ‘Innervisions’ alone, Stevie Wonder should be acknowledged for enriching all of our lives. But, Gil Scott-Heron has reminded me that Stevie Wonder should be acknowledged for so much more.

This is a truly stunning version of ‘Living For the City’ – Stevie on fine growling form